Save the article for later!

Grab the PDF copy of the article for easy offline reading.

Overview

Space exploration presents an extraordinary physiological challenge to the human body. In the absence of Earth’s gravity, every organ system of the human body must adapt to an environment it was never designed for. From disorientation and motion sickness, cardiovascular conditioning, blurred vision, to the loss of bone and muscle, the consequences of microgravity are wide-ranging and complex.

Over the past 5 decades, medical research—both in orbit and through ground-based analogs—has significantly deepened our understanding of how microgravity alters human physiology and has guided the development of countermeasures to protect astronauts’ health. This article summarizes the major medical effects of microgravity, the underlying mechanisms that drive them, and the countermeasures currently in place or under investigation to mitigate these challenges.

Introduction

On Earth, the human body has evolved under a gravitational force of 9.8 m/s², or 1 G. Every aspect of our physiology is adapted to this constant downward pull—our musculoskeletal system, cardiovascular regulation, fluid distribution, and even vision. Space exploration, however, exposes humans to prolonged periods of microgravity, where gravity levels fall below 1 G. Most of the human spaceflight experience comes from a 0 G environment in which mechanical loading is essentially absent. To illustrate, on extraterrestrial bodies such as the Moon or Mars, gravity exists only as a fraction of Earth’s—about 1/6 on the Moon and 1/3 on Mars. Because the body undergoes physical deconditioning whenever gravity is reduced, extended exposure to microgravity presents a major challenge for every astronaut.1

Over 5 decades of research have deepened our understanding of how microgravity alters human physiology and have guided the development of countermeasures to protect astronaut health. The following sections examine the major medical challenges associated with microgravity, explain the biology behind them, and review the current strategies used to preserve astronaut performance and safety in space.

Space Adaptation Syndrome (SAS) and Space Motion Sickness (SMS)

Transitioning from one gravity field to another is no small matter. It affects spatial orientation, coordination, and locomotion. While the human body can adapt to environmental changes—including shifts in gravitational forces—the adaptation takes time, and until it is complete, symptoms such as nausea, visual illusions, and disorientation may occur.2 Collectively, these effects are known as SAS.

SAS typically involves fluid shifting from the lower extremities to the face and upper body and can cause nasal stuffiness, headache, reduced appetite, and general malaise.3 Motion sickness symptoms may also develop.

Motion sickness arises when there is a mismatch between perceived and expected motion. A classic Earth-based example occurs when riding in a car or below deck on a ship: the body senses movement, but the surrounding environment appears still. The exact pathophysiology remains uncertain, but it is thought to involve overstimulation of the vestibular system—the sensory apparatus in the inner ear that informs the brain about balance, head position, and movement.4 Interestingly, individuals lacking a functional vestibulo-cochlear system are immune to motion sickness.3

SMS is a part of SAS, and it specifically describes motion sickness symptoms developing in some space crew members during the first few days of their spaceflight.2,5

Predicting who will develop SMS is not possible: some individuals prone to car sickness feel completely fine in space, while others without any history of motion sensitivity may experience symptoms.6 The prevailing hypothesis links SMS to microgravity’s altered effects on the vestibular system, where actual motion patterns—such as floating instead of falling in 0 G—differ markedly from what the brain expects. Cephalad fluid shifts may also contribute.3,5

SMS severity ranges from mild to severe and usually lasts from 2 to 4 days.5 While the condition is largely self-limiting, it reduces the work efficiency of astronauts during the first few days of space flight. To address this, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological countermeasures have been proposed. Among medications, promethazine and scopolamine have been shown to be especially promising in reducing SMS symptoms. However, their side effects–including fatigue, drowsiness, and impaired coordination–pose significant risks in the high-stakes environment of space, where vigilance and motor performance are essential. Attempts have been made to mitigate these drawbacks by pairing anti-motion sickness drugs with stimulants such as amphetamine; however, further research is needed to fully understand the underlying mechanisms, safety, and effectiveness of these combinations.7

Cardiovascular Adaptation and Fluid Shifts

While most symptoms of SMS resolve as the body adapts to the microgravity environment, the underlying fluid shifts that contribute to these symptoms continue to influence other physiological systems. Nowhere is this more evident than in the cardiovascular responses to weightlessness, where the redistribution of fluids plays a central role in both short- and long‑term adaptations.

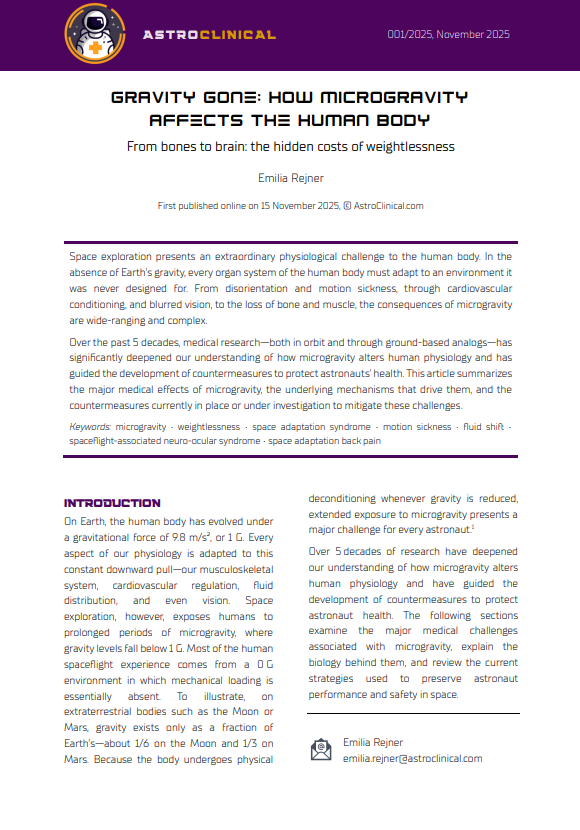

The cardiovascular system is highly sensitive to the environmental forces. In microgravity, the absence of the normal hydrostatic pressure gradient associated with upright posture on Earth results in a redistribution of blood volume towards the thorax and head (Figure 1).5 This cephalad fluid shift can cause facial puffiness, nasal congestion, and increased intracranial pressure (ICP).8 Moreover, one of the common medical problems noted in spaceflight is headache, affecting approximately 70% of astronauts who would not ordinarily experience it. This is thought to result from a combination of elevated ICP, impaired venous and lymphatic drainage, and increased cerebral pulse pressure or cerebral vessel dilation secondary to elevated CO2 levels found in the cabin atmosphere.5 Collectively, these physiological changes may also contribute to disrupted sleep patterns.8

Figure 1 Schematic Presentation of Microgravity-Induced Fluid Shifts

Schematic presentation of microgravity-induced fluid shifts. Stages highlighted in gold (stage 2 and 3) mark the changes happening in microgravity.

(1) On Earth, blood tends to accumulate in the lower body parts due to the constant downward pull of 1 G.

(2) Upon entering microgravity, fluids shift towards the thorax andhead (cephalad fluid shift).

(3) Over time, a reduction in red cell mass and circulating blood volume occurs.

(4) Upon reentering 1 G, fluids are shifted back from the head towards the feet.

Over time, a reduction in red cell mass and circulating blood volume occurs, and baroreceptor sensitivity declines.5,8 Cardiac atrophy and ventricular remodeling are likely to occur due to reduced load on the heart, ultimately leading to regression of the cardiac muscle. Although these changes may not manifest during spaceflight, they may have a considerable impact on astronauts’ health after returning to Earth.9

Long‐duration spaceflight missions are also believed to induce structural and functional alterations in the vasculature resembling age-related changes observed on Earth. An increase in arterial stiffness—an important predictor of cardiovascular risk—has been documented and appears consistent with elevated biomarkers of oxidative stress observed after 6 months of spaceflight.9

Fluid shifts towards the cephalic region in microgravity are further implicated in spaceflight‑associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS) (see below).8,10

Ultimately, all these changes eventually contribute to orthostatic intolerance upon return to Earth. Current countermeasures include oral rehydration prior to Earth’s atmosphere re-entry, in-flight exercise regimens, and the use of lower-body counterpressure garments. While these strategies alleviate some of the postflight symptoms, they are not fully effective. A clear unmet need remains for reliable methods to monitor fluid shifts, manage cardiovascular deconditioning, and minimize postflight orthostatic intolerance.5,8

Spaceflight-associated Neuro-Ocular Syndrome (SANS)

The same cephalad fluid shifts that challenge the cardiovascular system are also implicated in changes within the eyes and brain. These changes have given rise to one of the most intriguing and concerning conditions observed in long-duration astronauts—SANS.

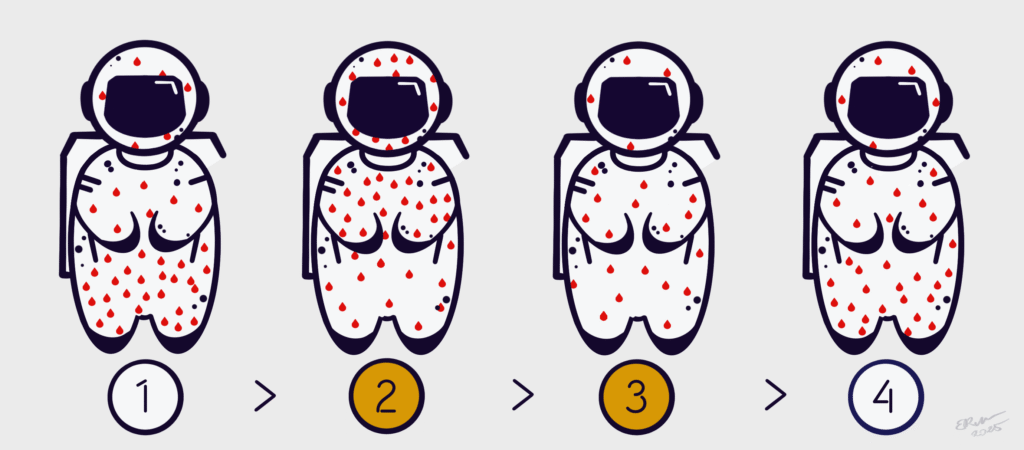

SANS is a condition caused by long-term exposure to microgravity that affects astronauts’ eyes and vision. It is characterized by swelling of the optic disc, folds in the choroid (the vascular layer of the eye), flattening of the back of the eyeball (globe flattening), shifts in vision (refractive changes), and persistent cerebral fluid shifts detectable even 6 months after flight (Figure 2).8

Symptoms include difficulty focusing on near objects, visual scotomas (appearance of areas in the visual field of partially diminished or entirely degenerated visual acuity), headaches, and blurred vision.11 Importantly, a formal definition of SANS has not yet been validated, and the clinical syndrome continues to be re-defined as new data emerge.12

Although the exact cause of optic disc swelling, globe flattening, choroidal folds, and fluid shifts in SANS remains unclear, 2 main—though not mutually exclusive—hypotheses have been proposed. The first suggests that these changes may result from a rise in ICP due to cephalad fluid shifts (see above). Increased ICP may be transmitted along the optic nerve sheaths, resulting in optic nerve sheath expansion, impaired axoplasmic flow, and globe flattening, resembling findings in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) on Earth. However, several factors argue against ICP elevation as the sole explanation of SANS. Astronauts with optic disc swelling and globe flattening generally do not experience severe headaches, transient visual obscurations, or double vision that typically accompany terrestrial IIH. Furthermore, optic disc swelling in astronauts is often asymmetric, whereas IIH usually presents with bilateral, symmetric edema. Additionally, if venous stasis from fluid shifts was the only driver, optic disc swelling would be expected to resolve quickly following upon return to Earth’s gravity—yet in some astronauts, swelling has persisted for up to 6 months post‑mission. Finally, postflight ICP measurements in astronauts have been only mildly elevated, rather than reaching the markedly high levels typically seen in IIH.12

The second hypothesis proposes compartmentalization of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) within the orbital optic nerve sheath. Traditionally, ICP and CSF composition were thought to be uniform across the brain, spinal cord, and optic nerve sheath. However, the unique anatomy of the optic nerve sheath may create a fragile flow equilibrium and a possible one-way valve‑like effect leading to localized pressure elevation within the orbital optic nerve sheath even without elevated ICP in the brain. According to this theory, during long-duration spaceflight, the upward shift of the brain and displacement of the optic chiasm (the part of the brain where the optic nerves cross) may exert a posterior pull on the optic nerve and globe. This traction could then compress CSF within the optic nerve sheath, resulting in localized pressure elevation and expansion.12 Countermeasures for SANS take a multi-faceted approach. These include, among others, selective use of acetazolamide for reduction of ICP, proper nutritional supplementation during spaceflight, and targeted exercise regimens. Interestingly, non-pharmacological therapies have also been tested, such as traditional Chinese herbal remedies. In bed rest studies, herbal intake was associated with wave-like decreases in near vision problems and intraocular pressure, though these effects have not yet been studied in astronauts during spaceflight.11

Figure 2 Spaceflight-associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome

Schematic illustration of the changes observed in spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS) — a condition caused by long-term exposure to microgravity that affects astronauts’ eyes and vision. In SANS, the affected eye typically shows signs of optic disc swelling, folds in the choroid (the vascular layer of the eye), and flattening of the back of the eyeball (globe flattening). One leading hypothesis proposes that these changes stem from an increase in intracranial pressure (ICP) due to cephalad fluid shifts. Elevated ICP may be transmitted along the optic nerve sheaths, resulting in optic nerve sheath expansion, impaired axoplasmic flow, and globe flattening.

Musculoskeletal Deconditioning

In addition to its effects on the nervous and cardiovascular systems, microgravity exerts equally profound effects on the body’s structural framework.

When not used, the musculoskeletal system deteriorates—this is observed in everyday life as a consequence of immobilization following injury or illness. In microgravity, the musculoskeletal system experiences continuous mechanical unloading; as a result, both bone and muscle decrease in quantity and quality. The rate and extent of bone loss during spaceflight are considerable, with reductions between 1 and 2% per month observed if countermeasures are not fully employed.5 Additionally, as an example, data from the Skylab missions showed decreases in total body mass of approximately 3 kg (6.6 lbs), with over 50% attributed to decreases in lean (fat-free) mass.13

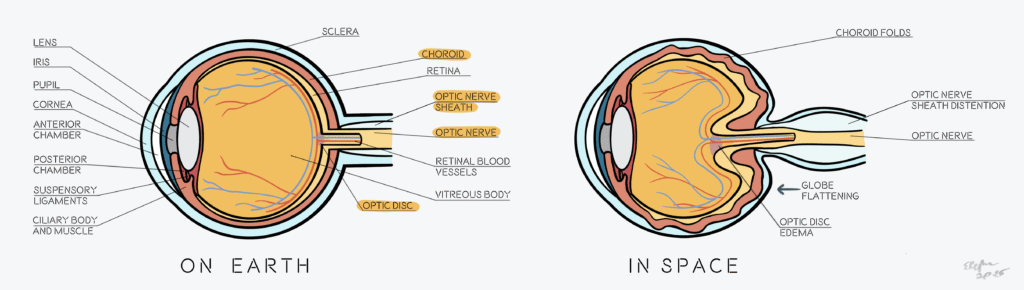

Another recognized consequence of microgravity exposure is space adaptation back pain (SABP). Studies indicate that 52% of astronauts experience some form of back pain in the first 2 to 5 days of spaceflight, with the pain being typically localized to the lumbar region. While 86% of the reported cases were mild and nearly all resolved by flight day 6, the pain was enough to hinder astronauts’ ability to complete tasks.10,14 Although the precise mechanism of SABP remains unclear, it is thought to be related to spinal lengthening and stretching of interspinous ligaments and associated nerve roots. Within the intervertebral discs, a loss of proteoglycan and collagen content is observed, accompanied by increased levels of inflammatory cytokines and the formation of annular tears, all of which compromise disc integrity. In the absence of gravitational compression, the discs also expand as they absorb fluids, further contributing to spinal elongation. Additionally, decreased lumbar lordosis has been observed, altering spinal curvature and alignment. Collectively, these changes result in a measurable increase in spinal column length—astronauts have been reported to “grow” by as much as 8 cm (3 in) during spaceflight (Figure 3).10,14–16

Figure 3 The Spine Changes in Microgravity

Adapted from: John Hopkins Medicine. Back Pain Common Among Astronauts Offers Treatment Insights for the Earth-Bound. October 21, 2021. Accessed October 13, 2025. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/newsroom/news-releases/2021/10/back-pain-common-among-astronauts-offers-treatment-insights-for-the-earth-bound

In microgravity, the musculoskeletal system experiences continuous mechanical unloading. This causes a range of structural and biochemical alterations in the spine that collectively contribute to space adaptation back pain frequently reported by astronauts during spaceflight. Both bone and muscle decrease in quantity and quality. Spinal lengthening and stretching of interspinous ligaments and associated nerve roots are also observed. Within the intervertebral discs, a loss of proteoglycan and collagen content is observed, accompanied by increased levels of inflammatory cytokines and the formation of annular tears, all of which compromise disc integrity. In the absence of gravitational compression, the discs also expand as they absorb fluids, further contributing to spinal elongation. Additionally, decreased lumbar lordosis has been observed, altering spinal curvature and alignment. Collectively, these changes result in a measurable increase in spinal column length—astronauts have been reported to “grow” by as much as 8 cm (3 in) during spaceflight.

Because the restoration of bone mineral density occurs at a rate estimated to be 5 to 6 times slower than the rate of loss, minimizing its deterioration during spaceflight is essential. Resistance exercise has proven to be the most effective countermeasure for preventing or minimizing bone loss not only in astronauts, but also in age-related osteoporosis on Earth.13 On the International Space Station, exercise regimens with the Advanced Resistive Exercise Device and treadmill result in much less loss of bone mass in astronauts and help with relieving the back pain.5,10 In contrast, these countermeasures appear less effective at maintaining muscle mass and function, likely due to suboptimal loading strategies and possible interference from concurrent, moderate-intensity training performed close in time to resistance training sessions.13

Empirically, astronauts have also found that assuming a tightly tucked position—with knees flexed to the chest—can provide some relief with SABP. Analgesics may also be used to manage the pain. Other preventive measures that can be combined with resistance exercise include massage therapy, nutritional supplementation to increase vitamin D and caloric intake, and neuromuscular electrical stimulation.10,14

Summary

Spaceflight strips away the constant gravitational force that has shaped human evolution. In doing so, it reveals the remarkable adaptability—and vulnerability—of the human body. The transition to microgravity disrupts spatial orientation and balance, alters cardiovascular dynamics and fluid distribution, and drives bone resorption and muscle atrophy—all of which not only challenge astronauts’ comfort and performance in space, but also compromise postflight recovery and mission readiness.

Over decades of research, a range of countermeasures have been developed to mitigate these effects. Structured exercise regimens, pharmacologic interventions, and mechanical aids like lower-body negative pressure suits have all proven valuable in maintaining astronaut health. Yet, despite these advances, no existing countermeasure fully prevents the deconditioning caused by prolonged exposure to microgravity.

As space missions grow longer and more ambitious, gaining a deeper understanding of how the human body adapts to microgravity—and refining the countermeasures that protect it—has become increasingly urgent. Continued innovation in this field is essential to ensure that humanity’s expansion into space remains not only sustainable and safe, but also biologically achievable.

References

- Barratt MR, Kuypers M. Spaceflight environment and biodynamic forces. In: Gradwell DP, Wilkinson ES, eds. Ernsting’s Aviation and Space Medicine. Sixth Edition. 6th ed. CRC Press; 2025:335-350. doi:10.1201/9781003033882-20

- Delft University of Technology. Why do astronauts suffer from space sickness? ScienceDaily. May 23, 2008. Accessed October 13, 2025. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/05/080521112119.htm

- Ogunniyi AA. Motion Sickness. MSD Manual Professional Version. March 2025. Accessed October 13, 2025. https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/injuries-poisoning/motion-sickness/motion-sickness#Etiology_v1115145

- Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, et al., eds. The Vestibular System. In: Neuroscience. International Sixth Edition. 6th Edition. Oxford University Press; 2018:287-301.

- Vanderploeg JM, Jennings RT. Commercial human space travel. In: Gradwell DP, Wilkinson ES, eds. Ernsting’s Aviation and Space Medicine. Sixth Edition. 6th ed. CRC Press; 2025:375-387. doi:10.1201/9781003033882-22

- Leadbeater C. “The next astronaut on the Moon will be a woman.” The Telegraph. June 10, 2020. Accessed October 13, 2025. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/activity-and-adventure/steve-smith-astronaut-interview/?ICID=continue_without_subscribing_reg_first

- Khalid A, Prusty PP, Arshad I, et al. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological countermeasures to Space Motion Sickness: a systematic review. Front Neural Circuits.Frontiers Media SA. 2023;17. doi:10.3389/fncir.2023.1150233

- Nova Southeastern University. Weightless Associated Cephalad Fluid Shifts; The Potential to Evaluate Venous and Lymphatic Dysfunction (NIID). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2024. Accessed October 13, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06405282

- Azariah J, Terranova U. Microgravity and Cardiovascular Health in Astronauts: A Narrative Review. Health Sci Rep.John Wiley and Sons Inc. 2025;8(1). doi:10.1002/hsr2.70316

- Barratt MR, Araujo SV. Space adaptation, clinical issues and countermeasures. In: Gradwell DP, Wilkinson ES, eds. Ernsting’s Aviation and Space Medicine. Sixth Edition. 6th ed. CRC Press; 2025:351-374. doi:10.1201/9781003033882-21

- Prospero Ponce C. Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-Ocular Syndrome (SANS).; 2025. https://eyewiki.org/Spaceflight-Associated_Neuro-Ocular_Syndrome_

- Lee AG, Mader TH, Gibson CR, et al. Spaceflight associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS) and the neuro-ophthalmologic effects of microgravity: a review and an update. NPJ Microgravity.Nature Research. 2020;6(1). doi:10.1038/s41526-020-0097-9

- Comfort P, McMahon JJ, Jones PA, et al. Effects of Spaceflight on Musculoskeletal Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis, Considerations for Interplanetary Travel. Sports Medicine.Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH. 2021;51(10):2097-2114. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01496-9

- John Hopkins Medicine. Back Pain Common Among Astronauts Offers Treatment Insights for the Earth-Bound. October 21, 2021. Accessed October 13, 2025. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/newsroom/news-releases/2021/10/back-pain-common-among-astronauts-offers-treatment-insights-for-the-earth-bound

- Belavy DL, Adams M, Brisby H, et al. Disc herniations in astronauts: What causes them, and what does it tell us about herniation on earth? European Spine Journal.Springer Verlag. 2016;25(1):144-154. doi:10.1007/s00586-015-3917-y

- Patron M, Neset M, Mielkozorova M, et al. Markers of Tissue Deterioration and Pain on Earth and in Space. J Pain Res. 2024;17:1683-1692. doi:10.2147/JPR.S450180